Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) has become a major topic in the NFL. The degenerative brain disease linked to repetitive head trauma causes memory loss, rage, mood swings, and in some cases, suicidal ideation. Doctors were only able to diagnose CTE postmortem, but that could soon change. Researchers at Evanston's NorthShore University HealthSystem believe they found traces of CTE in a former football player while he was still alive, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Four years ago, those researchers and other scientific organizations announced they had used brain scans to detect the hallmark of CTE in ex-NFL players while they were still alive, a technique that promised to spur more accurate diagnoses, and possibly new treatments. The scans indicated the presence of tau, a protein that builds up over damaged brain cells. Scientists cautioned that the results needed to be confirmed as the only definitive diagnosis could be made by examining brain tissue after a person's death.

Dr. Julian Bailes, a NorthShore neurosurgeon, said Wednesday that confirmation has arrived. In a paper published last week in the journal Neurosurgery, Bailes and other researchers reported that one of the former players who underwent a scan had his brain examined after he died — and sure enough, the tissue revealed he had been suffering from CTE.

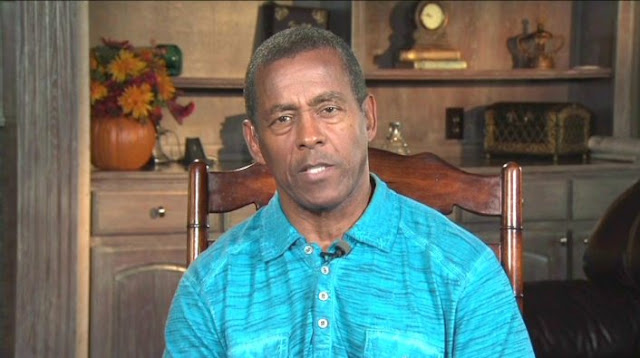

The player was unnamed in the study, but lead author Dr. Bennet Omalu confirmed to CNN that the subject of the case was former NFL player, Fred McNeill who died in 2015.

Omalu is credited with first discovering CTE in professional football players. He was portrayed by actor Will Smith in the 2015 movie "Concussion." Last year, Omalu told CNN that McNeill underwent the tau-detecting brain scan. After McNeill’s death, Omalu said he found signs of CTE in the athlete’s brain tissue.

The Neurosurgery paper says its subject played football for 22 years, including 12 in the NFL. McNeil had only one reported concussion, suffered when he was in college. When McNeil was done playing, he went through law school, joining a firm and becoming a partner. He was dismissed a few years later for poor performance.

The same thing occurred two more times before McNeil finally stopped practicing law and filed for bankruptcy. By the age of 59, he was showing distressing behavioral traits researchers believe are signs of CTE: memory loss, depression, a lack of impulse control and a bad temper. Two years later, his motor skills deteriorated until he couldn’t feed himself. Toward the end of his life, McNeill was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a disease that causes muscles to weaken and waste away, along with presumptive CTE. He died at 63-years-old.

More research is needed to corroborate the result, but if it holds up, Bailes said it could be a pivotal step in finding a way to help people with the condition.

Critics have said the protein can also highlight another protein called amyloid, which may be indicative of Alzheimer's or other forms of dementia. Omalu, however, noted that in CTE, tau makes distinctive patterns in the brain.

Omalu is in the process of raising more money to start phase 3 of the clinical trial to further test the technology. A definitive test could have a major impact on NFL players and other athletes in contact sports.

“If there’s ever a treatment developed, you can test the response to it,” Bailes said. “If you can trust the scans, you can tell a football player he shouldn’t keep playing, or tell someone in the military he can’t (be exposed to) explosions.”

Source: Chicago Tribune

Comments

Post a Comment